Episode 21: November 27th, 1922

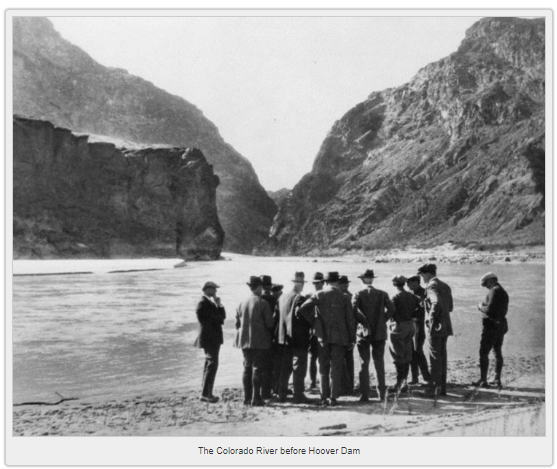

A century ago in Colorado River Compact negotiations: Heading Home

By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

After signing the Colorado River Compact on Friday, Nov. 24, 1922, the commissioners and their advisors returned to their home states. The compact would not become effective until it had been ratified by the legislatures of each of the states and the United States Congress. It was now time to prepare reports, answer questions, and work for state approval.

The ratification process was difficult. It would take 78 months before Congress finally approved a six-state pact and 22 years before all seven states agreed to it.

Arizona: Norviel

Arizona’s Winfield Norviel had the most difficult path ahead. Governor-elect George Hunt was opposed to the compact. Norviel knew that his job as the state’s water commissioner would be ending soon after Hunt took office. It’s a credit to Norviel that he simply didn’t tell the other commissioners that, given Hunt’s position, Arizona was not interested in agreeing to a compact, pack his bags and go home. Instead, he went back to Arizona and advocated for ratification. Hunt was reelected in 1924, again in 1926, lost in 1928, then won for the last time in 1930, always championing his opposition to the pact. Norviel died in 1935, nine years before Arizona ratified the compact.

Utah: Caldwell

Utah’s R.E. Caldwell returned to Salt Lake City and wrote a detailed report recommending ratification of the compact. The Utah legislature quickly complied. Caldwell resigned as State Engineer on July 1st, 1924, to “attend to personal business.” There is no evidence in the record that Caldwell stayed involved in Colorado River issues after his resignation. George Dern, who defeated Charles Mabey in 1924 for governor became Utah’s point man on the Colorado River. Caldwell died in 1959.

California: Mcclure

California’s W. F. McClure returned to Sacramento and wrote a short report. With the help of the Imperial Irrigation District, he obtained a clean ratification on February 3rd, 1923. In 1925, the California Legislature made its approval of the compact contingent upon Congressional approval of the Boulder Canyon Project. McClure never developed an effective working relationship with nor gained the full trust of the Imperial Irrigation District officials and the other Southern Californians with interests in Colorado River. He was a critic of the All-American Canal Project. McClure died in 1926. To represent the state on Colorado River matters California created the five-member Colorado River Commission in 1927 which became the Colorado River Board of California in 1937.

New Mexico: Davis

New Mexico’s Stephen Davis wrote a short report recommending ratification and, like Utah, its legislature quickly ratified the compact. On the same day that it approved the Colorado River Compact, February 7th, 1923, it also ratified the La Plata River Compact. The compact which covers a small tributary of the San Juan River shared by New Mexico and Colorado was negotiated by Carpenter and Davis and signed on November 27th. During the negotiations, Davis, who had resigned from the New Mexico Supreme Court when he was named its Colorado River Compact Commissioner, gained Hoover’s respect and confidence. In 1923 he became Solicitor of Hoover’s Department of Commerce. He later practiced law in New York from 1928 until death in 1933.

Nevada: Scrugham

James Scrugham, who had been elected Governor in November 1922, returned to Carson City and wrote a short report. Nevada’s legislature became the first state to ratify the compact on January 27th. He lost his bid for reelection in 1926. From 1932 – 1942 he was Nevada’s sole member of the U. S. House of Representatives. He was elected to the U. S. Senate in 1942, serving until his death in 1945.

Wyoming: Emerson

Wyoming’s Frank Emerson wrote a detailed report. The Wyoming legislature ratified the compact on February 9th, 1923. Emerson also became a governor, elected both in 1926 and 1930. As governor, he was actively involved in Colorado River matters, pressing Congress for approval of the compact and authorization of the Boulder Canyon Project. Emerson died while in office in 1931.

Colorado: Carpenter

Colorado’s Delph Carpenter returned to Greeley, Colorado where he also wrote a very detailed report, but ratification by his state was not easy. In March he had to write a supplemental report and call on Hoover to help him address several questions. Colorado ratified the compact on April 3rd, 1923. After Hunt was reelected Governor of Arizona in 1924, Carpenter became convinced that Arizona would not ratify the compact, so he became the quarterback of the six-state approval process that was implemented in 1928 when Congress passed the Boulder canyon Project Act. Carpenter, heralded as the father of interstate water compacts, was afflicted with Parkinson’s disease. He became bed-ridden in 1933 and died in 1951.

Chairman Hoover

Commission Chairman Herbert Hoover worked with the other commissioners to obtain ratification by their states. In 1928, he was elected as the 31st President of the United States. As president, on June 25th, 1929, he issued a proclamation declaring the Boulder Canyon Project Act effective. The act provided Congressional approval of the compact and authorized the construction of Boulder Dam, now Hoover Dam, and the All-American Canal. The legislation included a six-month window for California to limit its uses to 4.4 million acre-feet per year of Article III(a) water (plus ½ of the unappropriated surplus), for Utah to approve a six-state compact, and for the basin states to make one more attempt to make an agreement with Arizona. They failed. Hoover lost the 1932 election to Franklin Roosevelt in 1932. He died in 1964.

Reclamation’s Davis

The Commission’s primary technical advisor was Arthur Powell Davis, Director of the Reclamation Service. Davis returned to Washington D.C. where he helped Hoover address Congressional questions about the pact. More of a hands-on engineer and visionary than an administrator, Davis saw the compact as key to approval of the Boulder Canyon Project, which would reenergize his struggling agency.

The struggles ran deep. Two decades after the Reclamation Act laid out a vision for irrigating the West, projects were floundering, with farmers largely unable to repay the ten year interest free “loans” from the federal government that were the projects’ financing mechanism. The original ten year payback scheme had already been extended to twenty, but many irrigation projects were nevertheless abandoned because the irrigators could not pay.

On June 19th, 1923, the day after the Reclamation Service became the Bureau of Reclamation, Davis was dismissed by Interior Secretary Hubert Work. A year later Elwood Mead was hired as Commissioner. Under Mead, the Bureau of Reclamation would become a major agency building the world’s tallest dam, Hoover Dam, and the world’s largest hydroelectric project, Grand Coulee. Davis then became a consultant for California agencies. He died in 1933. In 1941, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes proclaimed that the dam being planned on Colorado River below Hoover dam at Bullshead (also known as Bullhead) would be named after Davis.

The Others

Two technical advisors, Colorado’s R. I. Meeker and Utah’s Dr. John Widstoe participated in both the 1922 and 1948 Compact negotiations. For the 1948 Upper Basin pact, Meeker was an advisor to Arizona.

As far as the authors can tell, no women were listed in the attendees to the Colorado River Compact negotiations. It is likely that Commission Secretary Clarence Stetson had clerical help. If so, they were never acknowledged.

There is no evidence that any Tribal members attended, or were even consulted, about the fate of the river in whose basins they had been living for time immemorial.