Episode 6: June 8, 1922

A hundred years ago in Colorado River Compact Negotiations: the Supreme Court Breaks the Logjam

By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

With a single statement, the United States Supreme Court changed the direction and tone of the compact negotiations:

|

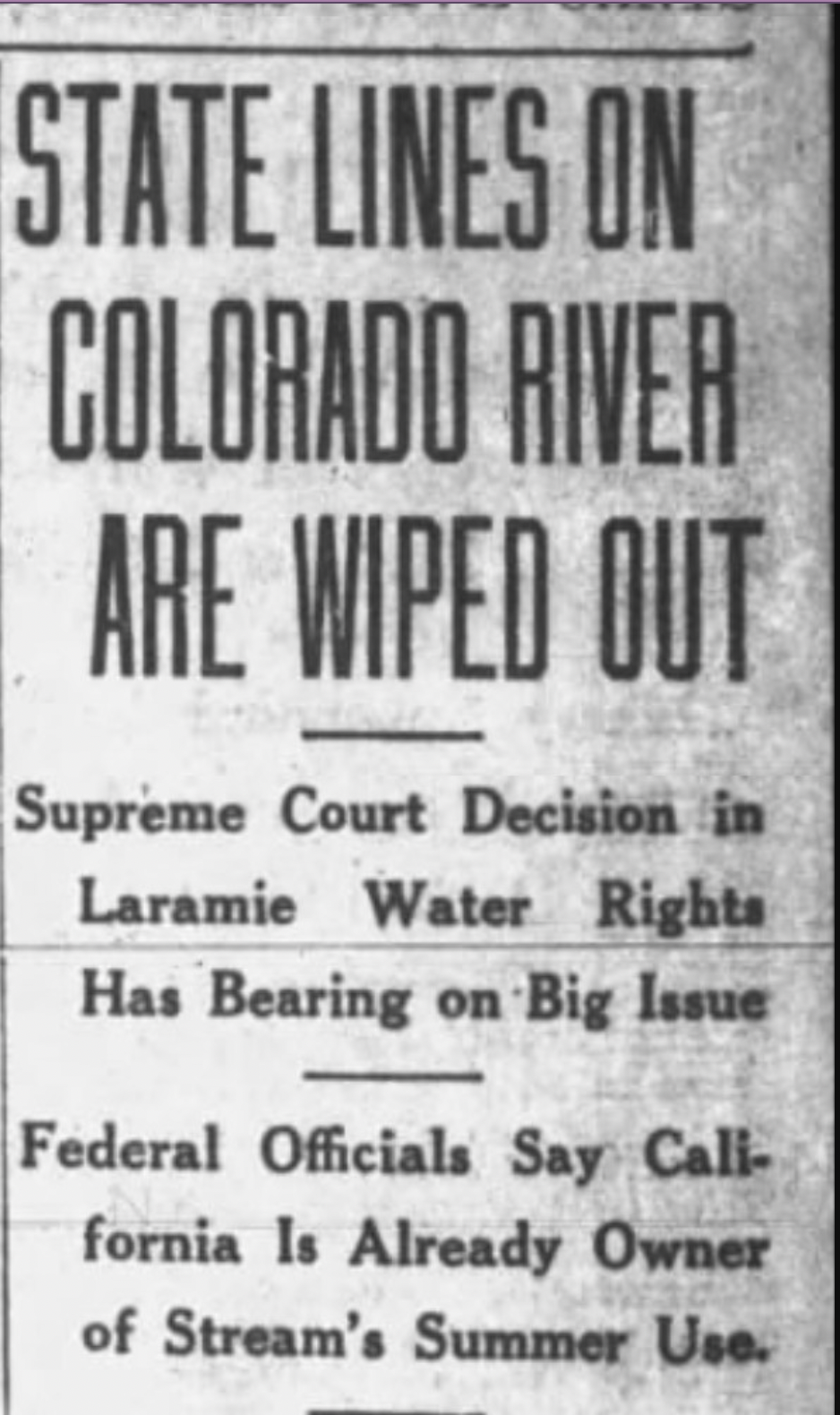

In a unanimous ruling, on June 5, 1922, the court issued its decision in Wyoming v. Colorado, ruling that Colorado could not develop waters of the Laramie River in a manner that ignored and injured downstream senior appropriators in Wyoming.  The decision, and its clear implications for the development of the Colorado River, echoed around the West. “State Lines on Colorado River Are Wiped Out”, blared a front page headline in the Salt Lake Tribune, adding “Federal Officials Say California is Already Owner of Stream’s Summer Use.”

The decision, and its clear implications for the development of the Colorado River, echoed around the West. “State Lines on Colorado River Are Wiped Out”, blared a front page headline in the Salt Lake Tribune, adding “Federal Officials Say California is Already Owner of Stream’s Summer Use.”

This was the risk that states in the river’s upper basin had long feared – that the doctrine of prior appropriation, used by the states within their own borders, might be determined to apply across state lines. Nervously, they all eyed California.

The Laramie, the river at the center of the court’s ruling, has its headwaters in the Northern Front Range Mountains about 40 miles west of Ft. Collins. From there it flows 280 miles north into Wyoming, reaching the North Platte River near Ft. Laramie, WY. Wyoming farmers and ranchers began using the river for irrigation purpose in the 1880s and 1890s. Within Colorado there is little irrigable land along the river’s path, but its elevation just happens to be about 225 feet higher than the Cache La Poudre River where the two rivers are a little more than two miles apart.

Thus, in 1909 two Colorado water companies, including the North Poudre Irrigation District, a client of Colorado’s Delph Carpenter, began construction of an 11,500 foot tunnel that would divert 800 cfs (essentially the entire river in low flow years) from the Laramie River into the already fully developed Poudre. In 1911 the State of Wyoming filed suit against Colorado to protect its existing irrigators.

Over the course of the eleven-year case, the Supreme Court held three oral hearings, the last in January 1921, only weeks before the Colorado River Commission first met. Wyoming’s basic argument was that Colorado’s proposed project would cause great damage and injury to its citizens who were already using the river for irrigation. Colorado’s basic argument was that it had a sovereign right to take and use any water within its boundaries without regard to the rights of states or individuals outside of Colorado. Both states used prior appropriation, but details of how the doctrine was administered were quite different. In Colorado water rights were adjudicated by the local district court. In Wyoming they were granted by a state Board of Control.

The opinion, written by Justice William Van Devanter, determined that since both states used prior appropriation, this doctrine would set the rule for the equitable interstate division of water on the Laramie River. The effect of the opinion was that to protect downstream senior appropriators in Wyoming, the Colorado project would be limited to an annual diversion of 15,500 acre-feet per year, about 20% of the original plan. The opinion was not a complete loss for Colorado. Wyoming had challenged the legality of the Colorado’s project because it was a transbasin diversion. The court found that there was nothing illegal with projects that move water.

As soon as the opinion was released, Colorado River Compact Commission Secretary Clarence Stetson sent copies of the opinion to the commissioners along with a six-point summary. For Colorado’s Carpenter, the loss was probably not a great surprise, but it was nonetheless a bitter defeat. He told his upper river colleagues that the decision left them badly exposed.

For the compact negotiations, the court decision required Carpenter to change his basic strategy. Up to this point, he and Utah’s Caldwell had held firm for a compact based on the concept that water projects in the Lower Basin would never interfere with water uses in the Upper Basin. The decision coupled with building public pressure for Congressional approval of a large storage reservoir to control floods, regulate the river, and produce much needed hydroelectric power meant that it was now time for Carpenter to propose a more practical alternative. He turned his attention to a concept proposed by Reclamation Service Director Arthur Powell Davis at the Los Angeles field hearing – a compact based on dividing the use of the river’s waters between two basins.

Stetson’s goal was to get the Commission back together in August. Hoover had asked New Mexico Governor Merritt Mechem for a recommendation on where they might meet in relative seclusion. Mechem found such a place, but finding a date that would work for Hoover and the other commissioners would push the meeting date out to November – stay tune.

Photo credit: Salt Lake Tribune, June 8, 1922